I

have to keep reminding myself, how small the place was. It was less

than a mile via Whitechapel Road between Aldegate (above, middle left) and the London

Hospital (above, upper right). And from a midway mark on that road, less then a twenty

minute walk in any direction encompassed all of Whitechapel,

Spitafields and Waping, the three poorest parishes in London.

Contained within that tiny circle were some 800,000 hungry,

exhausted, sickly, desperate people, living short, brutal, filthy

lives. Capitalism offered them few opportunities, and the ones it did

demanded first that they take advantage of each other. Religion

offered only the peace of resignation. Justice was a tool the

powerful used to remain poweful .

Life, liberty and happiness were available only if you

could afford them. And the wealth of those that could rested largely on the

backs of the people of the East End of London. The Victorian age was defined by

its hypocrisy, the sins of its age no less gilded in London, than in

Mark Twain's America.

Thus

it was a short sad walk pushing the police ambulance from George Yard, a

few block where Wentworth began Montague Street where the mortuary (above, green box, lower left) a half block from the Whitechapel

Union Workhouse.

About 7:00 that morning the cart was admitted through the

Eagle Place gate (above) and then had to wait while the gate keepers sent for

Robert Mann, the 53 year old workhouse inmate who was authorized to

open the mortuary for incoming bodies.

In

his life Robert Mann had been a dock worker, but either through

injury or illness, Robert's mind was injured

and left easily confused. He was no longer able to hold a job. He had

lived in the Workhouse for almost a decade now. He helped in the

kitchen, and in the men's ward of the hospital, mopping up, removing

waste and bodies. That Tuesday afternoon, Robert opened the mortuary a

second time to admit two nurses. They stripped and washed the body of

the unknown murder victim, and were the first to clearly see the

brutality done to her.

When they were finished the nurses stood by

while a photo was taken of the victim's pale blood drained face. Then

they left the body under a sheet on the dissecting table in the post mortem room and Robert

Mann locked the door behind them.

During

late Tuesday afternoon, 7 August, 1888, Detective Inspector Edmund

Reid had gone back to the Blackwell Building on George Yard (above), and

started knocking on doors. First he re interviewed the Hewitts, the

building superintendent and his wife, who lived on the ground floor.

They confirmed what they had told Constable Barrett. The dead woman

had never been a resident, and had never before been seen about the

building.

Inspector Reid then spoke to the woman in Apartment 37,

Louisa Reeves, the wife of John Saunders Reeves, who had found the

dead woman at 4:45 or 4:50 that morning. Lousia Reeves told Detective

Reid there had been several fights on Wentworth street that Monday

night, as was to be expected, what with it having been a “Bank

Holiday”. It was the last holiday of the summer. The couple had

heard the first shouting about 11:30, and then again half past

midnight, and then a third fight broke out about 1:00 am. The couple

had watched from their balcony overlooking Wentworth Street, while

the police broke up all three brawls. one after another.

The

resident of Apartment 35, Mr. Alfred George Crow, made his living as

a licensed driver of a hackney cab. The Bank Holiday had been a busy

work day for the 25 year old, and he did not get home until 3:00 am

on the morning of Tuesday, 7 August. He had seen a “person” on

the stairs, whom he assumed was sleeping. Since this was not unusual, he took little note of it, going straight to bed. He did not realized

a murder had occurred until 9 that morning, when he had gotten up,

and gone out to buy either food or gin.

At

7:30 that night, Inspector Reid caught Mrs. Elizabeth Mahoney

returning from her job at the Stratford matchbook factory, just

behind the Workhouse. The 25 year old soft spoken woman and her

husband John lived in Apartment 47, directly above Alfred Crow. She

said they had spent the day celebrating with her sister, and had not

returned home until about 1:40 that Tuesday morning. Elizabeth had paused in

their apartment just long enough to take off her hat and cloak,

before going downstairs again to buy some dinner (or gin) at a chandler's shop one block north on Thrawl Street (above). Elizabeth said the

errand had taken no more than five minutes, before she came home

again, climbing the same staircase just before two in the morning.

She saw no one on the stairs, she said, living or dead, and did not

learn of the murder until ten that morning.

Inspector

Reid took note that no one heard any screams or shouting after one

that morning, despite the Hewitts apartment being at the foot of the

stairwell. And given Mr. Crow's and Mrs. Mahoney's testimony, the

murder must have occurred between 2:00 am and 3:00 am. Because of the

lack of calls for help, it seemed likely that the victim had known

her killer. But until he knew the name of the first, he had little

chance of finding the name of the second.

Reid

wrote up a description of the victim, and had it dispatched to the news papers, who would publish it the next morning. The female victim was

about 37 years old, 5 feet 3 inches tall, with dark hair and a dark

complexion, wearing an old dark-green skirt, brown petticoat, long

black jacket, brown stockings, a black bonnet, and side-sprung boots.

It was a proven, plodding police approach. But Inspector Reid was

about to be offered a short cut that would throw his case completely

off track.

The

red herring appeared in the form of Police Constable Thomas Barrett,

who showed up early for his Tuesday evening tour at the Leman Street station. Speaking to Inspector Reid, Barrett said he was bothered by an incident which

occurred while he was walking his beat at 2:00 am on that Tuesday

morning. He spotted a soldier loitering on Wentworth street (above), near the

entrance to George Yard. Barrett thought he might be a guard to insure no interference with a robbery going on in the alley. When Barrett asked what he was doing there, the soldier

confessed to “waiting for chum who had gone up the alley with a

girl.” Because he believed the soldier, and because of the

directive regarding street walkers, Barrett merely told the soldier

to move along, and then continued his patrol.

Barrett described the

soldier as a Private between 22 and 26 years

of age, about 5 feet 9 inches tall, with fair complexion, dark hair

and a small brown mustache turned up at the ends. He was also wearing

a good conduct badge. It had happened three hours before the body

was discovered, but Barrett was sure he could recognize the soldier

again. Might it not have something to do with the murder? Desperate

for a lead, Reid thought it might.

On

Wednesday, 8 August, Reid escorted Constable Barrett to the Tower, where members of the Guards were paraded for his inspection. Looking for the soldier he had encountered outside of George Yard Tuesday morning, Barrett picked out one man, and then another. Under questioning, both men proved to have separate but equally iron clad alibis Reid was frustrated, but not surprised. The lead had led nowhere.

That same morning, Wednesday, 8 August, 1888, Dr. Timothy Robert Killeen

walked the five blocks from his surgery to the Old Montague Street Mortuary

to autopsy the body of the woman from George Yard. He

was supposed to be assisted by a nurse from the Workhouse hospital

ward, but none showed up. So the doctor relied on mortuary worker

Robert Mann and his assistant James Hatfield, a 68 year old resident

of the Workhouse.

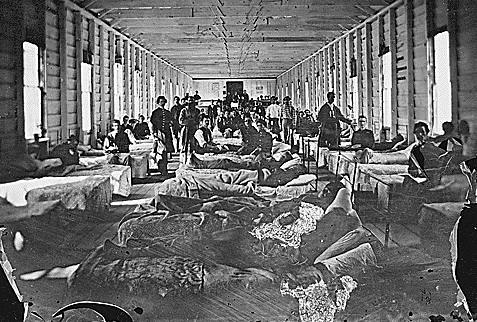

As usual for the Montague Street mortuary dissecting room (above) , conditions

were horrible. The lighting was bad, the room un-vented, and there was no ready source of water. Luckily it had

been a cool summer, because every surgeon in Whitechapel dreaded

doing an autopsy there in August.

Dr,

Killeen now counted 22 stab wounds (above). The left lung had been penetrated

in five places, the right lung in two places. The victim's fatty

heart had also been pierced. The liver had been penetrated five

times, the spleen twice, the stomach six times.

All but one of the

wounds had been inflicted by a pen knife, held, deduced Dr. Killeen ,

by a right handed person. But for some reason, on the death certificate (above), Dr. Killeen omitted

any details of the savage wounds to the victim's throat, or the slice

made just above her pubic bone.

Perhaps

the savagery of the assault on the woman was affecting him. Perhaps

it was the stench and dirty conditions in the mortuary. Perhaps

after three years laboring in the cesspit that was Whitechapel he was

finally feeling overwhelmed. If it was the latter, Dr. Timothy

Killeen would be far from the first or the last doctor to be "burned out" in Whitechapel. Within the year, Dr,

Killeen would return to his family home north of Limerick, Ireland.

He never wrote about his time in Whitechapel, nor his brush with the

murderer who would become known as Jack the Ripper.

-

30 -